Hiroshima , 6 August 2025

Dr Unni Krishnan*

The morning of August 9, 1945, was like any other—until 11:02 a.m., when the sky above Nagasaki was torn apart by a fire brighter than a thousand suns. In an instant, a five-year-old girl—her tiny frame no match for the force of the blast—was hurled to the ground by an invisible wave of death.

A FURNACE OF A THOUSAND SUNS

“I still remember the heat—it was like a thousand suns burning together,” says Chiyoko Motomura, now eighty-six, her eyes clouded with the horror of that day, as if it happened just yesterday.

The bomb—21 kilotons of plutonium, codenamed “Fat Man”—ripped apart buildings, families, and futures in seconds, marking one of the darkest moments in human history.

As glass exploded from the shattered door behind her, Motomura’s grandmother did what many could not: she moved. Wrapping her arms around the child, she shielded her with her own body. The glass shards pierced deep into her flesh, sparing the child but costing her life. “Glass pieces pierced my grandmother’s body,” Motomura recalls, her voice trembling. “She paid the price so I could live. I owe my life to her” Motomura told me during her visit to Cambridge University earlier this year.

What followed was not peace, but a prolonged nightmare. “Many people were burnt to the bone,” says Dr. Masao Tomonaga, a world-renowned radiation expert—and himself a survivor- and a member of UN’s Independent Scientific Panel on the Effects of Nuclear War.

The explosion killed tens of thousands in an instant. The death toll tells only part of the story. Those who survived—the hibakusha—endured lifelong agony: scorched skin, shattered families, cancer, stigma, silence. Bodies scarred by burns. Organs ravaged by radiation. Dreams haunted by firestorms and the cries of the dying. And beyond the physical pain was a crushing societal silence. For years, survivors were ostracized, their stories buried in shame and fear. “My parents never told their story. My mother never talked until I was twenty years old,” says Tomoko Watanabe, Hiroshima based peace activist and a second generation Hibakusha.

The bomb may have detonated in 1945, but for hibakushas the war never truly ended. Every memory is a scar. Every breath, a quiet act of resilience.

Their message is not one of vengeance—it is one of hope. Now in the twilight of their lives, the hibakusha carry a collective dream not just for them, but for all humanity: “Never again.” A world free of nuclear weapons. A world where no child is ever burned by a sun not of nature, but of man’s making.

Their voices may be fading, but their call is louder than ever. It is up to us—to listen, to remember, and to act. Peace is not a gift we inherit—it is a flame humanity is called to carry. We owe it to the past, and we fight for it in the present, so that no child ever inherits a sky on fire.

RAINBOWS OF ASH: UNVEILING THE TRUE COST OF HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI

On August 6 and 9, 1945, the skies above Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not just turn to fire—they became the crucibles of a new, horrifying era. The United States detonated two atomic bombs, “Little Boy” and “Fat Man,” unleashing an unprecedented scale of destruction. “Little Boy,” a 16-kiloton uranium bomb, obliterated Hiroshima. Just three days later, the 21-kiloton plutonium bomb, “Fat Man,” decimated Nagasaki.

The immediate aftermath was apocalyptic. In Hiroshima, an estimated 140,000 people perished by the end of 1945, with roughly half dying on that single devastating day. Nagasaki saw 70,000 lives extinguished by year’s end, impact reduced thanks to the terrain. The vast majority were civilians, many of them children. Entire families were instantly vaporized, leaving behind only shadows and scars. For those who survived the initial blast, death came agonizingly slow, from horrific burns, acute radiation sickness, and cancers whose full effects are still being studied today.

But the horror did not conclude in 1945. The suffering etched into the very fabric of existence continued. The hibakusha, the courageous survivors, bear the physical and emotional scars to this day. Many faced ostracism in post-war Japan, burying their unspeakable pain in silence. Yet, some, like the brave Tanaka, defied the silence. They chose to speak, becoming poignant voices for the dead, for the living, for the unborn and for all future generations, ensuring the world never forgets the actual cost of those infernal days.

“WE WERE BURNED, WE WERE POISONED, WE WERE FORGOTTEN.”

Terumi Tanaka, 93, speaks with quiet strength from his modest office in Tokyo. A survivor of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, he is one of the few remaining hibakusha—those who lived through the unimaginable.

For decades, Tanaka has dedicated his life to a single, urgent mission: making sure that what happened to him, and to hundreds of thousands of others, never happens again.

He is not alone in this effort. Other hibakusha, like Motomura, share their stories with courage and conviction—keeping the memory alive so that future generations may live free from the shadow of nuclear war.

“The atomic bombs were instruments of mass killing,” said Tanaka. “If used again, they could destroy all of humanity,” he warned me during our conversations in February 2025. Listening to him is not just a history lesson—it is bearing witness to a pain so deep it reshapes your understanding of war, of survival, and of peace. Every sentence he utters is etched with grief, but also with defiant hope. He is one of the last voices of a vanishing generation—yet he speaks not for the past, but for our future.

Tanaka is one of the few who refused to remain silent. In 2024, he stood before the world to accept the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of Nihon Hidankyo, the national platform of atomic and hydrogen bomb survivors and a movement for the total abolition of weapons of mass destruction. It was not a moment of triumph—it was a warning.

His presence on that stage was more than symbolic—it was a warning, and a plea. A reminder that the horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki must not become a chapter we close, but a lesson we learn—urgently, permanently.

The danger is far from over—it’s right here, right now. In a world already on fire, the threat of nuclear war looms closer than ever.

Today, there are over 12,000 nuclear warheads in the world. More than 4,000 are ready to launch within moments. Russia has threatened their use in Ukraine. An Israeli cabinet minister has spoken of nuclear weapons in the context of Gaza. The unthinkable is being spoken aloud again.

Tanaka’s words cut through this rising tide of danger: “There should be no weapons on earth that can kill tens of thousands of people in one full swoop” Tanaka told me. Powerful words that remind that we may be the last generation with the power and the responsibility to prevent another nuclear war.

THE MOON THAT KNEW NO WAR: TANAKA’S CHILDHOOD BEFORE THE BOMB

“When you’re a child,” Tanaka Terumi said, a mischievous smile lighting up his 93-year-old face, “you can say anything and play anything.”

We sat in his quiet, modest office in Tokyo—far removed from the rugged hills and wild bushes of his childhood. He grew up in a single-parent home. His father was in the military. He lost his father when he was five. After his father’s death, the family—his mother, older brother, and two younger sisters—moved back to their ancestral town of Nagasaki.

As we spoke, it was not the Nobel Peace Prize winner in front of me, nor the celebrated anti-nuclear activist. For a moment, it was just a boy remembering a simpler time—when the sun rose, the moon returned, and the seasons kept their quiet promises, bringing comfort in their steady, predictable rhythm.

“There weren’t many toys or new things like kids have today,” he said. “But every child had their own ideas.” He spoke fondly of making taketombo—bamboo dragonflies—and running up hills and closer the moon pretending to be Tarzan. “I made my own,” he laughed, “and climbed the mountains like a wild boy.”

To prepare for the interview, I turned to a group of curious schoolchildren never a shy bunch when asking big stuff—always brave, often hilarious, and wonderfully direct. They gave me a list of questions for the 93-year-old gentleman, ranging from (a) What did you do as a child to feel like a child? (b) What was your favourite game and why? (c) Did you get better at it over time? (d) What was your favourite childhood song—and could you sing it?

Tanaka was visibly delighted. “No one has ever asked me such questions,” he said, “not in all my years of interviews with journalists or scholars.” And then, with a twinkle in his eye, he answered.

He remembered how he got better at crafting bamboo dragonflies and how much he longed to fly kites but could not. “There just wasn’t enough space (to fly kites”) he said.

He paused, and then quietly hummed a tune—an old military song from his childhood. His gaze drifted for a moment, perhaps to the memory of a father he barely knew, perhaps to the boy he once was.

And then came the fire.

“My aunt’s family lost five people to the bomb,” he said, his voice turning solemn. “I saw dozens of bodies… hundreds of injured.” He was just thirteen when the world changed in a flash of light and a wave of heat. That moment—the burning of a city, the screams, the silence—left a mark on him that never faded.

But instead of being swallowed by grief, Tanaka chose to speak. To organize. To remember not just for himself, but for others. From the ashes of that day, he became a powerful voice for peace—a tireless advocate for a world without nuclear weapons. A hibakusha. A Nobel Peace Prize laureate. A witness to humanity’s darkest hour, and a light guiding us away from repeating it.

And yet, in that quiet Tokyo room, with a child’s questions and the afternoon sun warming the window, Tanaka was just a boy again—remembering how he once believed he could fly.

80 YEARS SINCE THE BOMBS: A CALL FOR PEACE IN A WORLD ON FIRE

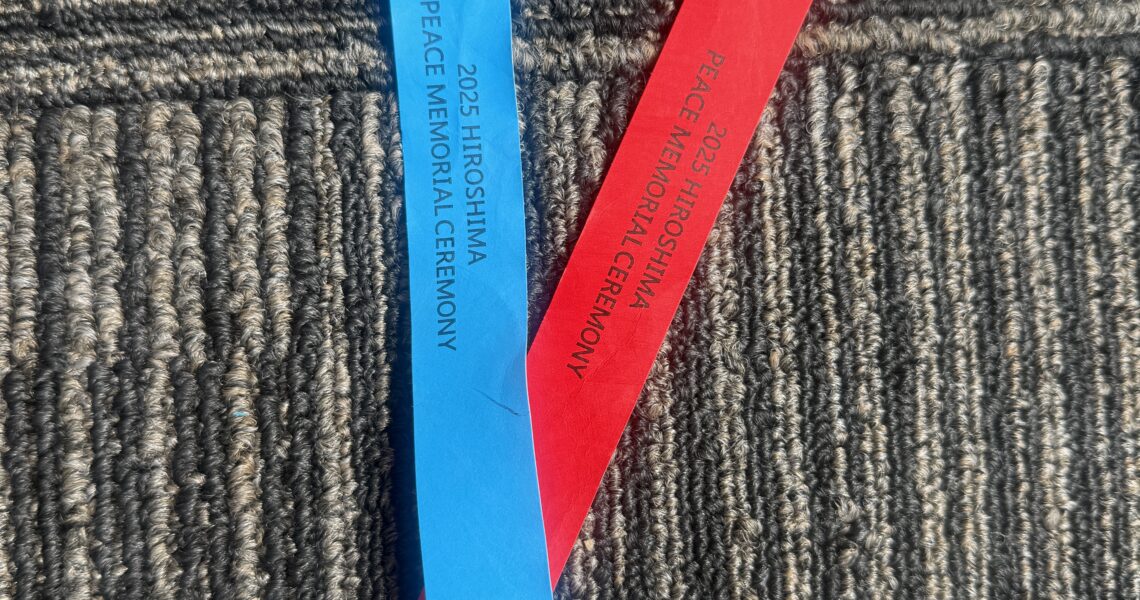

In August 2025, Hiroshima and Nagasaki will mark 80 years since nuclear bombs devastated their cities. Survivors—Hibakushas—and peace activists will gather at the epicentres of destruction not just to mourn the dead, but to honour resilience and reignite resistance to war and nuclear weapons. Their voices matter more than ever.

The nuclear threat is no relic of history. With conflicts escalating across continents, the world is closer to catastrophe than we admit. Armed conflicts have risen by 175% since 2010. In 2023 alone, seventy-eight countries were involved in wars beyond their borders. The warning signs are everywhere, yet the world remains alarmingly complacent.

“The risk of using nuclear weapons – intentionally or otherwise is as high as it has ever been – if not higher.” said Melissa Parke, Executive Director of International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize-winning campaign. To mark 80 years since the nuclear bombings and to honour over 30,000 children killed, ICAN, Peace Boat Japan, and Watanabe have launched a Children’s Peace Memorial to share their stories and call for urgent action.

As a humanitarian who has worked in Afghanistan, Iraq, Sri Lanka, Ukraine, and Gaza, I have seen the human cost of war. I remember Manzoor, a 14-year-old in Mazar-I-Sharif whose legs were blown off by a landmine. His mother, holding back tears, told me, “A war is a funeral in slow motion.” I also remembering meeting Abdul, a soft-spoken 16-year-old child soldier who once dreamed of becoming a pilot—until someone handed him a gun.

UNICEF reports that over 473 million children are now living in or fleeing from conflict zones. If you put all such children in a single country, that will be the third most populous country in the world. Nineteen percent of the world’s children—twice the share in the 1990s. Wars have turned playgrounds into battlefields and childhood into trauma.

In Gaza today, children are dying not just from bombs, but from deliberate starvation—used as a brutal weapon of war by the Israeli military. The deterioration of human values, International Humanitarian Law, and humanitarian principles has turned war zones into killing fields. The world’s failure to uphold humanity and human dignity marks a new moral low.

During our meeting in her office in Hiroshima this week, Watanabe told me “The upcoming commemorations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki are more than ceremonies. They will be global calls to end war, abolish nuclear arms, and choose peace before it’s too late.”

Peace activists such as Watanabe and Hibakushas are urging all nations to help build a safer world for future generations by signing the Treaty on the Prohibition of nuclear weapons—the first legally binding international agreement that fully bans nuclear weapons, with the ultimate goal of their total elimination.

A THOUSAND PAPER CRANES, ONE HOPE FOR HUMANITY:

Motomura believes that a world free of war is necessary and possible. “Peace begins with the courage to imagine a different future and is built through a lifetime of quiet resilience and acts of humble resistance” she says. It is the greatest tribute we can offer to those who perished, and the deepest responsibility we owe to those yet to be born.

As we spoke, Motomura shared the story of Sasaki Sadako—a year old little girl. Though she survived the initial blast in Hiroshima, she fell ill from radiation-induced blood cancer.

From her hospital bed, Sadako folded paper cranes —each one a fragile cry for life, hope, and peace. This was inspired by a Japanese legend that promises a wish to anyone who folds a thousand of them. Her wish was simple and profound: to live and for peace to prevail.

Despite pain and exhaustion, she folded crane after crane—using medicine wrappers, scraps, even food labels. She reached 1,000 before her young life ended at just 12 years old. Her paper cranes became a symbol of hope, grief, and a child’s desperate plea for a peaceful world.

When I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in February 2025, I stood before a bronze statue of Sadako holding a paper crane above her head, surrounded by thousands of colourful paper cranes sent by children from around the world. I was humbled and heartbroken. Each crane whispered a message: remember, resist, and never repeat.

We owe it to Sadako—and every child lost to war—to ensure her wish is fulfilled. Humanity must choose life over annihilation. Let us fold not just paper, but our resolve, into action.

Motomura’s words and Sadako’s story are reminders that peace is not a dream—it is a choice. Made again and again, in small acts, quiet voices, and unyielding resolve. A thousand folded paper cranes say: Never again.

*Global Humanitarian Director, Plan International